Surgical techniques included in this booklet

Surgeon to tick which techniques required before giving to patient:

Technique

- Anterior cervical corpectomy

- Anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion

- Posterior cervical laminectomy

- Posterior cervical laminotomy

- Posterior cervical laminoplasty

- Posterior cervical skip laminectomy

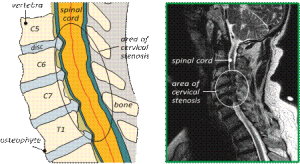

Following your recent MRI and consultation with your spinal surgeon, you have been diagnosed with a narrowing of your cervical spinal canal (cervical stenosis). This is usually due to the degeneration (wear and tear) of the spine.

The normal spinal column has a central canal (passage) through which the spinal cord passes down. To each side of the canal, spinal nerve roots branch out at every level. The spinal cord and nerve roots are surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and are contained within a membrane, or covering, called the dura mater, rather like the thin layer that covers a boiled egg.

There are seven bones (vertebra) in the cervical spine (neck). In between each bone is an intervertebral disc which acts as both a spacer and a shock absorber. Over time, as disc degeneration (wear and tear) occurs, the disc will lose water and height and sometimes bulge and as such, close the bony passage where the nerve root and spinal cord passes through.

In cervical stenosis, the spinal cord becomes compressed by arthritic joint swelling and bony overgrowths (osteophytes) or bulging of the intervertebral discs that narrow the spinal canal. This pressure can damage the spinal cord (myelopathy). Rarer causes include cysts or tumours in the spinal canal.

The spinal cord is like an electrical cable that takes messages back and forth from your body to your brain. It tells your muscles to move and gives your brain information about various sensations such as pain, temperature, light touch, pressure sensation and position of your arms.

Myelopathy is a generally progressive condition that develops slowly and is most commonly caused by spinal stenosis. Symptoms may not progress for years and then difficulties with coordination may suddenly increase.

In severe cases it can cause paralysed arms and legs or make someone wheelchair-bound or bed-bound.

Cervical stenosis: Diagram and MRI scan

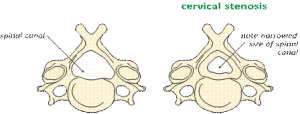

Normal vertebra Vertebra with

Nerve root pain is felt in the area of the body that the nerve supplies after it leaves the spine. Pain in the arm (brachial neuralgia) is very like sciatica but comes from the nerves as they leave the neck. Often it is the symptoms of arm pain, tingling, weakness or numbness that prompts someone with this condition to seek medical treatment but then the signs of spinal cord damage and myelopathy can be found, through a medical history and physical examination.

People with cervical stenosis and myelopathy may have one or more of the following symptoms:

- numb, clumsy hands (pins and needles or a ‘fizzing’ feeling);

- a heavy feeling in their legs;

- inability to walk at a hurried pace;

- balance issues (such as unsteadiness and stumbling when walking or knocking into things – rather like if you were ‘drunk’);

- difficulty with fine motor skills (such as handwriting or buttoning a shirt); and /or

- intermittent ‘electric shock’ type pains into the arms and legs, especially when bending their head forward.

Cervical myelopathy is a serious problem. The pressure and damage to the spinal cord will not go away and the symptoms would most likely continue to get worse without surgery.

The main aim of surgery is to remove the pressure (decompression) and the subsequent damage to the spinal cord as soon as possible to stop the progression of the condition. The results from surgery are variable however, as some people have more extensive damage than others beforehand. An operation before severe damage has occurred usually provides the best results for the patient.

After surgery, some patients may regain:

- some spinal cord function;

- modest improvement in their hand function and walking capabilities;

- some feeling in their hands. (If there is a lot of numbness prior to the surgery, it probably won’t go away completely); and

- improvement of the pain in their arms. Relief from neck pain however, is more difficult to predict and it should not be regarded as the main aim of the surgery. It is therefore unlikely that this type of surgery would be performed for people suffering neck pain alone without experiencing other symptoms.

If the surgery simply prevents the progression of the spinal cord damage (myelopathy) and there is no loss of function due to the surgery, both the patient and the surgeon should consider it successful.

The operation

There are different techniques when performing an operation for a cervical stenosis. Expected outcomes from all methods are very similar and the choice of operation will be decided by your surgeon. The approach (way in) to the cervical spine can also vary from either the front (anterior) or back (posterior) of the neck, depending where most compression is coming from. Sometimes it is necessary to perform surgery from both the front and back, though usually at different times.

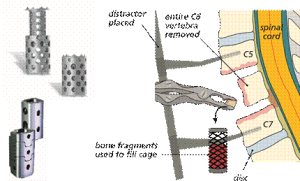

Anterior cervical corpectomy

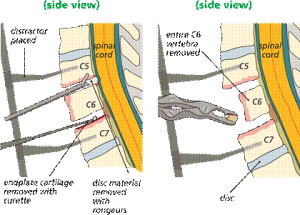

Cervical corpectomy (removal of bone) is often performed because of multiple level cervical stenosis due to bone spurs on the

vertebral bodies. The approach is made through an incision in the front of the neck, then the oesophagus (food pipe) and the trachea (windpipe) are retracted (held back) off the spine. A microscope is usually used at this point to give greater magnification of the structures. The surgeon then removes the cervical disc (discectomy) at either end of the vertebral body that needs to be removed (eg C5/6 and C6/7 discectomy to remove C6 vertebral body – see diagram B overleaf). More than one vertebral body may be removed.

Removal of the vertebral body enables the surgeon to remove any bony spurs pushing onto the spinal cord to ensure that the nerve roots and spinal cord have more room. The vertebrae are then replaced with a vertebral body cage or sometimes a solid piece of bone graft (called a strut graft). A metal plate can be applied to the front of the spine to add stability and prevent cage / graft dislodgement.

This approach to the spine has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

Stabilisation techniques used in anterior cervical corpectomy surgery

- Intervertebral fusion cage. This is like a hollow Lego brick which props up the space created between the two bones (vertebra). It is a tight fit and gives immediate stability. The cage is available in different width, height and depths to fit your spine exactly. It is made from carbon fibre, PEEK (reinforced plastic) or titanium metal. The cage can be filled with bone graft or artificial bone. It may be appropriate to fix the cage more robustly with screws into the bone above and below or to apply a metal plate to the front of the spine.

- Bone graft. This is used to fuse (join together) and stabilise the spine, often in conjunction with other techniques (e.g cage). When it is placed in the spine your new bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft. This is a biological process over 3 – 6 months, known as spinal fusion. There are several techniques to get the bone graft needed for spinal fusion:

- artificial bone (synthetic bone) These are bone-like substances and are most commonly used;

- patient’s own bone (autograft bone). This can be taken from the pelvis (iliac crest) if required or from the bone removed and bony spurs in the area of surgery; or

- donor bone (allograft bone). Donor bone graft does not contain living bone cells but acts as calcium scaffolding which your own bone grows into and eventually replaces.

Examples of vertebral, Vertebra removed body cages (side view)

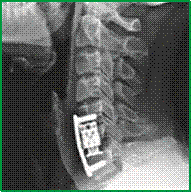

3 Anterior plate fixation. A metal (titanium) plate can be applied to the front of the cervical spine to add stability and prevent graft and /or cage dislodgement. It is screwed into the vertebral bodies above and below the surgical site. Titanium is a light metal and is compatible with MRI studies after the surgery.

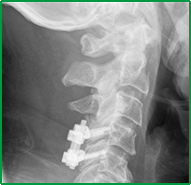

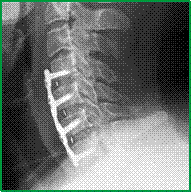

X-ray showing the plate and cage in position

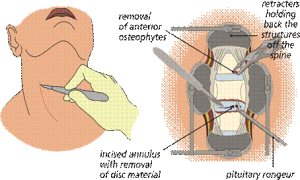

Anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion (ACDF)

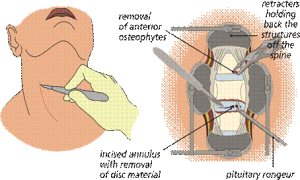

Cervical discectomy (removal of disc) and interbody fusion can be performed when there is either single or multiple level cervical stenosis due to degenerative disc protrusions causing narrowing in the spinal canal. The approach is made through an incision in the front of the neck, then the oesophagus (food pipe) and the trachea (windpipe) are retracted (held back) off the spine. A microscope is usually used at this point to give greater magnification of the structures. The disc space is then distracted (jacked up) to a more normal disc height to widen the canal for the nerve root and to help relieve the pressure. The surgeon then removes the cervical disc. More than one disc may be removed if necessary.

Removal of the disc also enables the surgeon to remove any disc material and bony spurs pushing onto the spinal cord to ensure that the nerve roots and spinal cord have more room. The disc spaces are then filled with bone graft and / or a cage which can contain bone graft. A metal plate is sometimes applied to the front of the spine to add stability and prevent graft dislodgement.

This approach to the spine has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

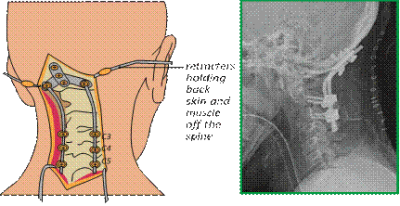

The incision is made to, The skin and muscles are held back, Expose the cervical spine, Off the spine before the disc is removed

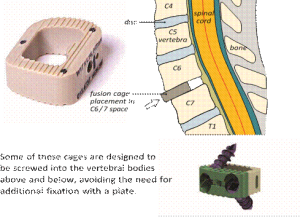

Stabilisation techniques used in anterior discectomy and interbody fusion (ACDF) surgery

- Bone graft. This is used to fuse (join together) and stabilise the spine, often in conjunction with other techniques. When it is placed in the spine your new bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft. This is a biological process over 3 – 6 months, known as spinal fusion. There are several techniques to get the bone graft needed for spinal fusion:

- artificial bone (synthetic bone). These are bone-like substances most commonly used in intervertebral fusion cages; or

- patient’s own bone (autograft bone). This can be taken from the pelvis (iliac crest) if required or from bony spurs in the area of surgery; or

- donor bone (allograft bone). Donor bone graft does not contain living bone cells but acts as calcium scaffolding which your own bone grows into and eventually replaces.

- Intervertebral fusion cage. This is like a hollow Lego brick which props up the disc space between the two bones (vertebra). It is a tight fit and gives immediate stability. The cage is available in different width, height and depths to fit your spine. It is made from PEEK (reinforced plastic), carbon fibre or titanium metal. They can be filled with bone graft or, more commonly, artificial bone and are used in anterior cervical discectomy spine surgery.

Example of a fusion cage and the placement into the disc space (side view)

3 Anterior plate fixation.

A metal (titanium) plate can be applied to the front of the cervical spine to add stability and prevent graft and/or cage dislodgement. It is screwed into the vertebral bodies above and below the surgical site. Titanium is a light metal and is compatible with MRI studies after the surgery.

X-ray showing the plate and cages in position

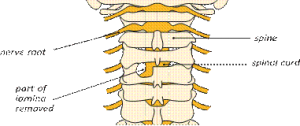

Posterior cervical laminectomy

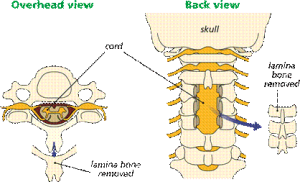

Cervical laminectomy (removal of lamina) may be performed because of multiple level cervical stenosis due to bone spurs or ‘thickened’ ligaments on the lamina (bony arch) at the back of the neck.

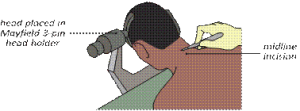

Because surgery is performed with the patient lying on their front and to ensure that the head and neck are kept very still throughout the operation, it is necessary to apply temporary pins into the skull which are attached to a special clamp (Mayfield clamp), allowing the head to be suspended securely over the operating table. These are usually put in and removed while the patient is under anaesthetic or heavily sedated (asleep).

The surgical approach

The approach is made through an incision in the midline at the back of the neck. The muscles are then held apart to gain access to the bony arch and roof of the spine (lamina). A high-speed burr (like a dentist’s drill) can be used to make a trough in the lamina and then the lamina bone and any bone spurs are removed, allowing the spinal cord to ‘float’ backwards and give it more room.

roof of the spine (lamina). A high-speed burr (like a dentist’s drill) can be used to make a trough in the lamina and then the lamina bone and any bone spurs are removed, allowing the spinal cord to ‘float’ backwards and give it more room.

Laminectomy

Removing the cervical lamina completely can cause problems with the stability of the cervical spine. If the facet joints between each vertebra are involved during laminectomy surgery, the neck may begin to tilt forwards causing problems later. To prevent this from happening, the surgeon may add stability to the spine by placing a rod on the side of the spine and attaching them by screws.

Stabilisation techniques used in cervical laminectomy surgery

1 Lateral mass screw fixation. Small screws are placed into the back of the cervical spine angled out into the bone, away from the spinal canal, into what is known as the lateral mass. These screws then act as firm anchor points to which rods can be connected. This acts like an internal scaffolding system which prevents movement at the segments being fused. After the bone graft grows and fuses to the spine (after many months), the rods and screws are no longer needed for stability. However, most surgeons do not recommend removing them except in rare cases.

This technique has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

X-ray showing the lateral mass screw fixation in position

2 Pedicle screw fixation. Like the lateral mass fixation, screws are placed into the vertebral body through the part of the vertebrae called the pedicle and attached to rods. This system allows the surgeon to fix the cervical spine down to the thoracic spine which has more stability. Because of the position of the vertebral artery in the cervical spine, these screws are usually only placed in the lower cervical vertebrae and thoracic vertebrae but then the rods can be linked onto the lateral mass screw system.

In very rare circumstances it may be necessary to use an occipital plate. This system enables the base of the skull (occiput) to be fixed to the cervical spine.

Technical variations for surgery from the back of the cervical spine

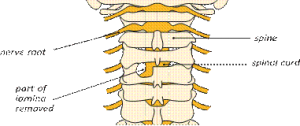

Posterior cervical laminotomy

This procedure is generally selected when the main problem is arm pain and there is little or no spinal cord compression and damage (myelopathy), or neck pain. With a similar approach to cervical laminectomy, the surgeon will try and avoid the need to stabilise the spine by not completely removing the lamina bone and its natural support by only removing a small portion of it (usually on one side but can be both). Sometimes this can be performed through a narrow tube to reduce muscle dissection and injury (minimally invasive (tubular) laminotomy).

Laminotomy

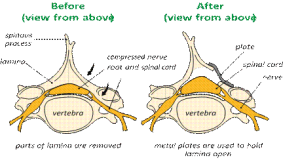

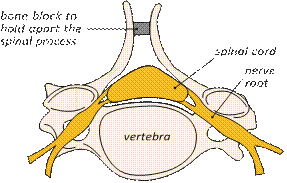

Posterior cervical laminoplasty

With a similar approach to cervical laminectomy, the surgeon will avoid the need to stabilise the spine by not completely removing the lamina bone. The bone is only partially cut on one side and completely cut on the other. This creates a hinge on one side of the lamina partially cut and a small opening on the other side. The lamina is then wedged open by inserting a spacer made from bone, metal or plastic on the ‘open’ side. Often referred to as an ‘open door’ laminoplasty. Another type called ‘French door’ laminoplasty is performed by creating hinges on both sides of the lamina and opening in the centre of the lamina, resembling French style patio doors. These techniques increase the space available for the spinal cord and take the pressure off it.

‘Open door’ laminoplasty

Posterior cervical skip laminectomy

Again, with a similar approach to the back of the neck as with cervical laminectomy, this technique is less damaging to the muscular structures. Once the skin incision is made at the back of the neck, the muscular attachments are left undisturbed. The spinous process (bony tip to the lamina) is split down to the lamina which is then removed, relieving pressure off the spinal cord. In this procedure, alternate levels in the neck can be decompressed, while the others ‘skipped’ as the name implies. In this way, there is no requirement for stabilisation.

Risks and complications

As with any form of surgery, there are risks and complications associated with this procedure. These include:

- Damage to a nerve This occurs in less than 1 out of 100 cases of primary surgery, but is much more common in revision or ‘re-do’ surgeries where injuries can occur in up to 10 out of 100 cases. If this happens, you may get weakness in the muscles supplied by that particular nerve root and /or numbness, tingling or hypersensitivity in the area of skin it supplies;

- Tearing of the outer lining or covering which surrounds the nerve roots (dura). This is reported in fewer than 5 out of 100 cases. It may occur as a result of bone or the disc being very stuck to the lining and tearing as it is lifted off. Again, it is much more common in ‘re-do’ surgery. Usually the hole or tear in the dura is repaired with stitches, a patch or a special glue. If the puncture or hole re-opens then you may get CSF leaking from the wound, headaches or, very rarely, meningitis. Although rare, the problems of leakage can persist. This could result in you having to return to theatre to enable the surgeon to revise the repair of the dura but the risk of a second operation being required within a few days or weeks is less than 0.05%;

- Recurrent symptoms;

- You must inform your consultant if you are taking tablets used to ‘thin the blood’, such as warfarin, aspirin, rivaroxiban or clopidogrel. It is likely you will need to stop taking these before your operation. Taking medication like non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) could also increase your risk of bleeding and your surgeon will advise you if you need to stop taking these in advance of your operation. If your operation is scheduled with only a week’s notice, please check with your consultant or nurse which drugs need to be stopped to prevent your surgery being delayed;

- Superficial wound infections may occur in up to 4 out of 100 cases. These are often easily treated with a course of antibiotics. Deep wound infections may occur in fewer than 1 out of 100 cases. These can be more difficult to treat with antibiotics alone and sometimes patients require more surgery to clean out the infected tissue. This risk may increase for people who have diabetes, an impaired immune system or are taking steroids. As our skin and hair harbour bacteria, it is often necessary to shave the back of the hair when performing posterior cervical spine surgery. This prevents hairs falling into the wound during the operation. Men undergoing anterior cervical spine surgery who have a beard may be asked to shave before the operation but to be careful not to cut themselves and risk skin infections, as this could delay the surgery going ahead;

- blood clots (thromboses) in the deep veins of the legs (DVT) or lungs (PE). These occur when the blood in the large veins of the leg forms blood clots and may cause the leg to swell and become painful and warm to touch. Although rare, if not treated this could be a fatal condition if the blood clot travels from the leg to the lungs, cutting off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. It is reported as happening in fewer than 1 out of 100 cases. There are many ways to reduce the risk of a blood clot forming. The most effective is to get moving as soon as possible after your operation. Walk regularly as soon as you are able to, both in hospital and when you return home. Perform the leg exercises as shown to you by the physiotherapist and keep well hydrated by drinking plenty of water. Women are also advised to stop taking any medication which contains the hormone oestrogen (like the combined contraceptive or HRT) four weeks before surgery, as taking this during spinal surgery can increase the chances of developing a blood clot;

- problems with positioning during the operation which might include pressure problems, skin and nerve injuries and eye complications including, very rarely, blindness. Special gel mattresses and protection is used to minimise this;

- bone graft non-union or lack of solid fusion (pseudoarthrosis). This can occur in up to 5 out of 100 cases. See ‘Factors which may affect fusion’ section);

- possible complications associated with taking out bone graft from the iliac crest (pelvis) include graft site pain and damage to a sensory nerve that supplies sensation to the front of the thigh (the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve). Most surgeons however, will use cages and/or artificial bone to avoid this risk; and

- in the long term, or in years to come, pain can develop from problems at other levels in the neck.

There are also very rare but serious complications that in extreme circumstances might include:

- damage to the spinal cord and paralysis (the loss of use of the arms and legs, loss of sensation and loss of control of the bladder and bowel). This can occur through bleeding into the spinal canal after surgery (a haematoma). If an event of this nature were to occur, every effort would be made to reverse the situation by returning to theatre to wash out the haematoma. Sometimes, however, paralysis can occur as a result of damage or reduction of the blood supply to the nerves or spinal cord and this is unfortunately not reversible;

- a stroke, heart attack or other medical or anaesthetic problems;

- and extremely rarely, death, as a result of damage to major blood vessels around the spine, which is reported as happening in 1 out of 10,000 cases; or

- general anaesthetic fatal complications which have been reported in 1 out of 250,000 cases.

Anterior corpectomy – specific risks and complications:

- cerebral vascular accident (CVA) (stroke). There is a slight risk when the cervical vertebral body is removed that the vertebral artery (blood vessel) that runs on the side of the spine is injured. This could lead to a cerebral vascular accident (stroke) and/or life threatening bleeding;

- bleeding in the wound and swelling in the windpipe (laryngeal oedema), which could result in difficulty breathing or swallowing. This is rare but if it occurs, it may be necessary to take you back to theatre to try to stop the bleeding;

- bone graft/cage movement can occur in up to 2 out of 100 cases, with 1 out of 100 requiring re-operation. In extremely rare cases movement can cause severe damage and paralysis;

- damage to the trachea (windpipe) or oesophagus (food pipe). This is reported in fewer than 1 in 100 cases;

- injury to the small nerve that supplies the vocal cords. This can happen because of the retraction during the procedure and can cause temporary (or rarely, permanent) hoarseness of the voice. Retraction of the oesophagus can produce temporary difficulty and discomfort with swallowing. It is advisable to eat ‘soft’ food for a few days to help with this; and

- less than 1 in 100 patients can experience a droopy eyelid due to temporary stretching of a small nerve (sympathetic chain). This is not usually obvious and nearly always recovers.

Anterior discectomy – specific risks and complications:

- bleeding in the wound and swelling in the windpipe (laryngeal oedema), which could result in difficulty breathing or swallowing. This is rare but if it occurs, it may be necessary to take you back to theatre to try to stop the bleeding;

- bone graft/cage movement can occur in up to 2 out of 100 cases, with 1 out of 100 requiring re-operation. In extremely rare cases movement can cause severe damage and paralysis;

- damage to the trachea (windpipe) oroesophagus (foodpipe). This is reported in fewer than 1 in 100 cases;

- injury to the small nerve that supplies the vocal cords. This can happen because of the retraction during the procedure and can cause temporary (or rarely, permanent) hoarseness of the voice. Retraction of the oesophagus can produce temporary difficulty and discomfort with swallowing. It is advisable to eat ‘soft’ food for a few days to help with this; and

- less than 1 in 100 patients can experience a droopy eyelid due to temporary stretching of a small nerve (sympathetic chain). This is not usually obvious and nearly always recovers.

Lateral mass screw fixation – specific risks and complications

- cerebral vascular accident(CVA) (stroke). There is a slight risk when the screws are placed, that the vertebral artery (blood vessel) that runs on the side of the spine is injured. This could lead to a cerebral vascular accident (stroke) and/or life threatening bleeding; or

- damage to the spinal cord or nerve root causing paralysis.

Factors which may affect spinal fusion and your recovery

There are a number of factors that can negatively impact on a solid fusion following surgery, including:

- smoking;

- diabetes or chronic illness;

- obesity;

- malnutrition;

- osteoporosis;

- post-surgery activities (see note of recreational activities); and

- long-term (chronic) steroid use.

Of all these factors, the one that can compromise fusion rate the most is smoking. Nicotine has been shown to be a bone toxin which inhibits the ability of the bone-growing cells in the body (osteoblasts) to grow bone. Patients should make a concerted effort to allow their body the best chance for their bone to heal by not smoking, ideally 2 – 3 months before the operation. Your surgery may be delayed if you have not stopped smoking (or taking nicotine in another form) beforehand.

What to expect after surgery and going home?

Immediately after the operation you will be taken on your bed to the recovery ward where nurses will regularly monitor your blood pressure and pulse. Oxygen will be given to you through a facemask for a period of time to help you recover from the anaesthetic. You will have an intravenous drip until you can drink again after the surgery.

A drain (tube) may be placed near the surgical incision to prevent any excess blood or fluid collecting under the wound. It is also likely that you will be sitting up in bed immediately after the operation as this will help to reduce any swelling in your neck. If a drain has been used, it will be removed by the nursing staff when the drainage has stopped, usually the next day after surgery.

It is very normal to experience some level of discomfort or pain after the surgery. The nursing and medical staff will help you to control this with appropriate medication. The symptoms in your arms may fluctuate due to increased swelling around the nerves. As the nerves become less irritated and swollen, your pain should slowly start to settle. This can take up to eight weeks, or longer. It is important not to suddenly stop taking certain pain relief medication, such as morphine or neuropathic medication (gabapentin, pregabalin or amitriptyline). It will be necessary to gradually ‘wean’ yourself off them –your GP can advise you if necessary. As previously mentioned, any improvement in hand function or walking ability, may be slight and can occur slowly over the next year or so.

With anterior cervical surgery you may experience some temporary difficulty and discomfort when swallowing, a ‘soft’ diet for a few days will help ease this until your swallowing becomes more comfortable.

The ward physiotherapist will visit you after the operation to teach you exercises and help you out of bed. They will show you the correct way to move safely. Once you are confident and safely mobile, you will be encouraged to practise climbing stairs with the physiotherapist if this is appropriate. Once you are safe enough to manage at home you will be discharged, usually 1 – 2 days after surgery but this may need to be longer.

Please arrange for a friend or relative to collect you, as driving yourself or taking public transport is not advised in the initial stages of recovery.

Wound care

Options of skin wound closure depends on your surgeon’s preference, and include absorbable sutures (stitches), removable sutures or clips (surgical staples).

If you have removable sutures or clips, you will be seen by a nurse to remove them usually 10–14 days after posterior cervical operations and 7 days in anterior cervical surgery in the outpatient department.

If you have absorbable sutures, these still may need to be trimmed and will still require a wound check to take place. The ward staff or consultant secretary will inform you of the date for your appointment or if you are required to make an appointment with your GP practice nurse.

You may shower 48 hours after surgery if you are careful, but you must avoid getting the wound wet. Most dressings used are ‘splash-proof’, but if water gets underneath, it will need to be changed. A simple, dry dressing from a pharmacy is sufficient to use if a new dressing wasn’t provided on discharge, please make an appointment in this instance for a wound check and re-dressing with outpatients’/specialist nurse. Bathing should be avoided for a minimum of two weeks.

Please contact Nuffield hospital if you think your wound might be infected. Symptoms could include:

- redness around the wound;

- wound leakage;

- a high temperature or

- Increased pain at wound site

At a later stage once the wound has healed and been checked, if the scar is sensitive to touch, you can start to massage around the scar using an unperfumed cream or oil to encourage normal sensation and healing.

Driving

Normally you will be advised to avoid driving for 2 – 4 weeks or when you no longer require the neck brace if your surgeon has recommended one, but this can be adjusted depending on your recovery.

If you have no altered sensation or weakness in your arms and you can move your head around freely, then you may resume driving if you feel safe to do so but you must be confident to do an emergency stop.

It is advisable not to travel for long distances initially (no longer than 20 minutes) without taking a break to move about.

Recreational activities

It is important to keep as mobile as you can after surgery, so get up and move about regularly (every 20 minutes or so). Walking outside is fine but increase your walking distances gradually and be careful not to trip over when on uneven ground.

You will be advised to avoid lifting anything heavy, certainly for the first few weeks but maybe up to three months after your operation.

Please check with your consultant when you are able to resume specific activities such as swimming or golf, as the advice could range from between six weeks to three months or longer for contact sports. A graduated return to sport is the advisable. Your surgeon may advise you to avoid flying for six weeks (and long-haul flights for up to three months) because of the increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after surgery.

Work

Returning to work is dependent on both your recovery and your job. Most people are off work for an initial four weeks, but if you are in a strenuous job you may need up to eight weeks, again this may be adjusted earlier or later and according to your recovery or type of work. It is always sensible to discuss with your employer if you can return on ‘light duties’ or reduced hours at first. There is usually nothing to stop you doing computer / office work at an earlier date, as long as you can keep moving about. The hospital will issue you with a fitness to work (sick) certificate, you can request this whilst you are in hospital or can call the ward if you have been discharged, furthermore you can request this from your GP.

Follow-up

Your surgeon will advise you when you should attend clinic after your operation. It is common practice to have X-rays to check the bone healing and position of the stabilisation techniques used in surgery at these appointments. If you have any queries before your follow-up date, please do contact the nurse specialist or other member of your consultant’s team.

What is the British Spine Registry (BSR)?

The British Spine Registry aims to collect information about spinal surgery across the UK. This will help us to find out which spinal operations are the most effective and in which patients they work best. This should improve patient care in the future.

The Registry will enable patient outcomes to be assessed using questionnaires. These will allow surgeons to see how much improvement there has been from treatment.

This has worked for hip and knee joint replacements through the National Joint Registry. We need your help to improve spinal surgery in the UK.

What data is collected?

Your personal details allow the BSR to link you to the surgery you have had. They also allow us to link together all the questionnaires you complete. If you need any further spinal surgery in the future, details of previous operations will be available to your surgeon.

Personal details needed by the BSR are your name, gender, date of birth, address, email address and NHS number.

Your personal details are treated as confidential at all times and will be kept secure. This data is controlled by the British Association of Spine Surgeons (BASS) and held outside the NHS. Personal details will be removed before any data analysis is performed, retaining only age and gender. Your personal data and email address will not be available to anyone outside BASS and its secure IT provider. Anonymised data may be released to approved organisations for approved purposes, but a signed agreement will restrict what they can do with the data so patient confidentiality is protected.

Your personal data is very important, as this will allow us to link details of your diagnosis and surgery with any problems or complications after surgery. You may also be asked to complete questionnaires before and after surgery to work out how successful the surgery has been. This will only be possible if we can connect you to the questionnaires through your personal details.

Do I have to give consent?

No, your participation in the BSR is voluntary and whether you consent or not, your medical care will be the same. Your personal details cannot be kept without your consent. This will be obtained either by asking you to physically sign a consent form or electronically sign one through an email link to a questionnaire or at a questionnaire kiosk in the outpatient clinic.

You can withdraw your consent at any time or request access to your data by:

- Going to the patient section of the BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com; or

- Writing to us at the BSR centre. Please state if you are happy for us to keep existing data but do not want to be contacted, or whether you want your data to be anonymised (so it cannot be identified).

Research

Your consent will allow the BSR to examine details of your diagnosis, surgical procedure, any complications, your outcome after surgery and your questionnaires. These are known as ‘service evaluations’ or ‘audits’.

Operation and patient information, including questionnaires in the BSR, may be used for medical research. The purpose of this research is to improve our understanding and treatment of spinal problems. The majority of our research uses only anonymised information which means it is impossible to identify individuals. From time to time, researchers may wish to gather additional information. In these cases, we would seek your approval before disclosing your contact details. You do not have to take part in any research study you are invited to take part in and saying no does not affect the care you receive.

All studies using data from the Registry will be recorded on the BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com

Further information

The BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com contains more information, including details of any studies and any information obtained through the Registry data.

To contact the BSR, write to: www.britishspineregistry.com

The British Spine Registry

Amplitude Clinical Services

2nd Floor

Orchard House

Victoria Square

Droitwich

Worcestershire

WR9