Edited by Consultant Neurosurgeon Mr Al-Mahfoudh

Edited in 03/2022

Surgical techniques included in this booklet

Surgeon to tick which techniques required before giving to patient:

Technique Page

- Interbody fusion 6

- Bone graft 7

- Pedicle screw fixation 9

- ALIF 10

- TLIF 12

- PLIF 13

- LLIF / XLIF 14

- OLIF 15

Following your investigations and consultation with your spinal surgeon, you have been diagnosed with degenerative disc disease and the possibility of you undergoing a lumbar spinal interbody fusion has been discussed with you. This is an operation where a degenerative intervertebral disc is removed and the space fused (joined) together with a bone graft.

There are five bones (vertebra) in the lumbar spine (lower back). In between each bone is an intervertebral disc. The healthy intervertebral disc acts as both a spacer and a shock absorber and is composed of two parts: a soft gel-like middle (nucleus pulposus) surrounded by a tougher fibrous wall (annulus fibrosus).

The normal spinal column has a central canal (or passage) through which the spinal nerves pass down. At each vertebral level, spinal nerve roots branch out to each side. The solid spinal cord stops at the top of the lumbar spine (lower back) and from this point the nerves to the bottom and legs pass like a horse’s tail (the cauda equina) through the lower canal. The spinal cord, nerve roots and cauda equina are surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and are all contained within a membrane, or covering, called the dura mater, rather like the thin layer that covers a boiled egg,

Overhead view of an intervertebral disc (simplified)

Over time, the intervertebral discs lose their flexibility, elasticity and shock absorbing characteristics (disc degeneration). This disc degeneration can cause inflammation in the surrounding area and sometimes these discs’ can

be a source of continuing back pain, pain in the thighs and buttocks, stiffness, muscle tightness and tenderness. This is known as discogenic pain (pain arising from the disc). Occasionally, the tough outer layer of ligaments that surrounds the disc weaken and tear, causing the central gel to bulge into the nerve canal (termed a disc protrusion or prolapse), causing pain when it touches a nerve.

A nerve is like an electrical wire. It tells your muscles to move and gives your brain information about various sensations such as pain, temperature, light touch, pressure sensation and position of your leg. Lumbar nerve root pain or radiculopathy (often called sciatica) generally goes below the knee and is felt in the area of the leg that the spinal nerve supplies. Symptoms also associated with sciatica include altered sensation, pins and needles, burning, numbness or even weakness of the muscles in the leg the nerve supplies.

In rare cases the nerves which control your bladder, bowel and sexual function can be compressed. This is known as cauda equina syndrome (CES) and often requires urgent surgical intervention. Fortunately, immediate spinal surgery is only necessary in a few cases. However, it is vital that seek medical attention or attend the emergency department if you develop any red flag symptoms which include the following;

- Numbness around the saddle area (genitals, buttocks, between the legs)

- Urinary difficulties such as poor flow, urgency, retention of urine, loss of sensation when urinating

- Sciatica-like pain in both legs, or weakness in the legs

Sexual dysfunction or loss of sensation

Treatment varies depending on the severity of the condition. Most patients only require treatments such as physiotherapy and medication, combined with some lifestyle changes. Excess body weight will increase the load and pressure on the intervertebral discs and may exacerbate the problems, causing an increase in symptoms. Losing weight may be beneficial if a patient is obese.

For patients whose pain does not settle with treatment or less extensive surgery, such as a disc decompression, lumbar fusion surgery may be necessary. Surgery for lower back pain caused by degenerative disc disease is only considered an option for patients who:

- have not had sufficient pain relief from extensive non-surgical treatment (such as physiotherapy, medications and pain management programmes) for at least a year;

- have had recurrent disc protrusions causing symptoms of nerve compression;

- have undergone investigations to achieve a diagnosis that a specific disc is the pain generator and other possible causes of the lower back pain have been considered and ruled out; and

- once the risk factors which can negatively affect spinal fusion have been considered (see ‘factors which may affect spinal fusion’), as these may rule out this type of procedure as an option.

The aim of fusion surgery is to stabilize the painful motion segment and to stop movement at it. The expectation is not to ‘cure’ the spinal problem but to provide a good percentage improvement and relief of most of the symptoms. Good relief from back and leg symptoms following this type of surgery, usually occurs in approximately 70% of cases (up to 7 out of 10 people). This is not necessarily felt immediately but over a period of time (often several months). Sometimes however, when there is extensive numbness or weakness in the legs, this may persist (even with a technically successful operation).

The operation – interbody fusion

An interbody fusion operation is where the degenerative intervertebral disc is removed and the space is fused (joined) together using bone graft and a combination of other surgical techniques.

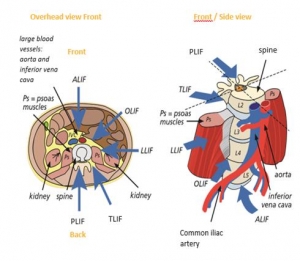

The approach (way in) to the lumbar spine can vary and the different surgical options for interbody fusion include: posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) also known as XLIF, oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) and anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), as illustrated below.

Expected outcomes from all the different surgical techniques are very similar. Your surgeon will decide the best approach and type of cage suitable to your condition in order to restore alignment and open areas in the disc space which may have collapsed, causing nerve root symptoms. They will take into consideration your symptoms (back pain and/or leg pain), previous surgery and your general body shape and fitness. They will also consider the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, including the risks associated with them. Sometimes it is necessary to approach from the anterior (front) or lateral side of the spine to position the cage but also to approach from the posterior (back) to use additional stabilisation techniques such as pedicle screw fixation (see below).

Stabilisation techniques

- Bone graft. This is used to fuse (join) the bones of the spine together in conjunction with other techniques which hold the spine stable while new bone is growing. When it is placed in the spine your new bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft. This is a biological process over 6 -12 months, known as spinal fusion. There are several techniques to get bone graft needed for spinal fusion:

-

- patient’s own bone (autograft bone). The bone which is removed during surgery can be used as a bone graft. If more is needed, for the most part, artificial (synthetic) bone is used, although it may be taken from the pelvis (iliac crest) if required;

- artificial bone (synthetic bone). These are bony like substances used in addition to patient’s own bone;

donor bone (allograft bone). Donor bone graft does not contain living bone cells but acts as calcium scaffolding which your own bone grows into and eventually replaces.

- Intervertebral fusion cages. This is like a hollow Lego brick which props up the disc space between the two bones (vertebra). It is a tight fit and gives immediate stability. The cage is available in different width, height and depths to fit your spine exactly. It is made from carbon fibre, PEEK (reinforced plastic) or titanium metal. They can be filled with bone graft or artificial bone if required and used in interbody fusion surgery.

Examples of fusion cages

In certain cases, it is necessary to fix the cage with screws into the bone above and below (used in ALIF surgery).

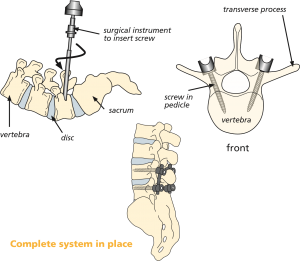

3 Pedicle screw fixation. This is a system of screws and rods which hold the vertebra together and prevents movement at the segment that is being fused, like an internal scaffolding system. Screws are placed into the part of the vertebra called the pedicle, which go directly from the back of the spine to the front, on both sides, above and below the unstable spinal segment. These screws then act as firm anchor points to which rods can be connected. After the bone graft grows and fuses to the spine (after many months), the rods and screws are no longer needed for stability. However, most surgeons do not recommend removing them except in rare cases.

Side view of pedicle screw

placement

Overhead view of pedicle

screw in vertebral body

4 Lateral plates. This is system which holds the vertebra together by using a metal plate which is screwed into the vertebral bodies from the side of the spine, above and below the disc space to be fused.

The surgical approach

1 Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF)

This is performed through an incision in the tummy. The abdominal contents lay inside a large sack (peritoneum) that can be retracted (moved to the side), allowing the surgeon access to the front of the spine without entering the abdomen. The large vessels (aorta, common iliac artery and vena cava) that lie over the front of the spine are carefully moved aside. Sometimes surgery is performed in conjunction with a vascular surgeon, who will mobilise the blood vessels if there are any concerns or difficulty with this.

After the blood vessels have been moved aside, a ‘window’ is cut in the anterior ligament and fibrous wall of the disc (annulus fibrosus). The disc material (nucleus pulposus) is then removed and the cage, containing bone graft, is placed in the space created. Some cages require placement of screws or blades into the vertebral body above and below them. Your own bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft.

This approach to the spine has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

Diagram of cage placement Cage in situ

X-rays showing ALIF cage in place, side and front views

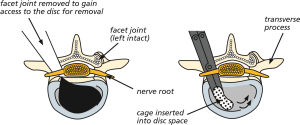

2 Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF)

This is performed through an incision in your back. The muscles are held apart (retracted) on one side to gain access to the bony arch and roof of the spine (lamina). Next, the facet joint, which is directly over the nerve root, is removed on one side to gain access to the disc. The side approached is usually the same as the leg symptoms which might be experienced, if appropriate, as this will enable the surgeon to explore the nerve root at the same time and ensure that there is no pressure on it (decompression). The disc is then removed right back to the bone edge of the vertebral body (end plates). Bone graft is then placed in the space created and/or within the cage and laid between the outer segment of the spine in between the transverse process (inter-transverse region). Your own bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft.

If bilateral leg symptoms are being experienced, then further surgery can be performed to remove the pressure off the opposite nerve root. To avoid retracting the other muscle off the lamina, a minimally invasive (tubular) decompression may be performed, which involves working through a narrow tube.

Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF)

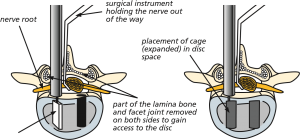

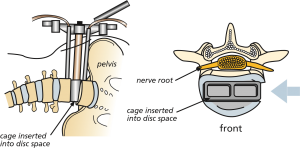

3 Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF)

The spine is approached through an incision in the midline of your back and the muscles are held apart (retracted) to gain access to the bony arch and roof of the spine (lamina). Next, part of the lamina bone and facet joints on both sides, which are directly over the nerve roots, are removed to gain access to the disc. This will also remove any pressure off the nerve roots (decompression). The disc is then removed, right back to the bone edge of the vertebral body (end plates). Bone graft is then placed in the spaces created and/or within the cages placed both sides and laid between the outer segments of the spine in between the transverse process (inter-transverse region). Your own bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft.

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF)

created for cage disc removed and space

4 Lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF / XLIF)

The spine is approached from the side of the body, through an incision just above the pelvis. (This approach is not suitable to fuse the lowest lumbar disc because the pelvis would be in the way). The abdominal contents which lay inside a large sack (peritoneum) can be retracted (moved to the side), allowing the surgeon access to the side of the spine. A tubular instrument known as dilators is inserted into the incision and allows a blunt probe to push through the psoas muscle (a large muscle that runs from the lower spine, wrapping around the pelvic area and attaching to the hip). Because nerves exiting the spinal canal are close to the psoas muscle, the surgeon will use neuromonitoring, the testing of nerves during surgery to make sure they are not damaged or irritated during the procedure. The disc is then removed, right back to the bone edge of the vertebral body (end plates). Bone graft is then placed within a cage and inserted into the disc space. Your own bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft. This approach to the spine has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

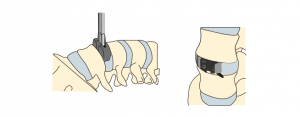

Lateral interbody fusion Lateral interbody fusion (LLIF / XLIF) approach (LLIF / XLIF)

5 Oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF)

The spine is approached through an incision to one side of the tummy. The abdominal contents which lay inside a large sack (peritoneum) can be retracted (moved to the side), allowing the surgeon access to the spine. A tubular instrument known as a dilator is inserted into the incision and allows a blunt probe to push through to the spine. (This approach avoids the psoas muscle and exiting nerves from the spine as in the LLIF/XLIF procedure and allows access to the lowest lumbar disc because it goes in front of the pelvis). The disc is then removed, right back to the bone edge of the vertebral body (end plates). Bone graft is then placed with a cage and inserted into the disc space. Your own bone will, over time, grow into the bone graft.

This approach to the spine has risks and complications which are specific to it and are listed below the general ones (see ‘Risks and complications’).

Risks and complications

- Damage to a nerve root. This occurs in less than 1 out of 100 cases of primary surgeries but is much more common in revision or re-do surgeries, where injury can occur in up to 10 out of 100 cases. If this happens, you may get weakness in the muscles supplied by that particular nerve root and / or numbness, tingling or hypersensitivity in the area of skin it supplies.

- Tearing of the outer lining or covering which surrounds the nerve roots (dura). This is reported in fewer than 5 out of 100 cases. It may occur because of the bone being stuck to the lining and tearing it as the bone is lifted off. Again, it is much more common in re-do surgery. Usually the hole or tear in the dura is repaired with stitches, a patch or a special glue. If the puncture or hole re-opens then you may get CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) leaking from the wound, headaches or, very rarely, meningitis. Although rare, the problems of leakage can persist. This could result in you having to return to theatre to enable

the surgeon to revise the repair of the dura but the risk of a second operation being required within a few days or weeks is less than 0.05%.

- Neuropathic pain (nerve pain) as a result of scarring around the nerve root.

- Problems with positioning during the operation which might include pressure problems, skin and nerve injuries and eye complications including, very rarely, blindness. Special gel mattresses and operating tables are used to minimise this.

- Superficial wound infections may occur in up to 4 out of 100 cases. These are often easily treated with a course of antibiotics. Deep wound infections may occur in fewer than 1 out of 100 cases. These can be more difficult to treat with antibiotics alone and sometimes patients require more surgery to clean out the infected tissue. This risk may increase for people who have diabetes, impaired immune systems or are taking steroids.

- Blood clots (thromboses) in the deep veins of the legs (DVT) or lungs (PE). These occur when the blood in the large veins of the leg forms blood clots which may cause the leg to swell and become painful and warm to the touch. Although rare, if not treated this could be a fatal condition if the blood clot travels from the leg to the lungs, cutting off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. It is reported as happening in fewer than 1 out of 700 cases. There are many ways to reduce the risk of a blood clot forming. The most effective is to get moving as soon as possible after your operation. Walk regularly as soon as you can, both in hospital and when you return home. Perform the leg exercises as shown to you by the physiotherapist and keep well hydrated by drinking plenty of water. Woman are also advised to stop taking any medication which contains the hormone oestrogen (like the combined contraceptive or HRT) four weeks before surgery, as taking this during spinal surgery can increase the chances of developing a blood clot.

- Surgeons try to minimise bleeding by using devices like diathermy, a technique which passes an electrical current into the wound to cause bleeding vessels to clot. You must however, inform your consultant if you are taking tablets used to ‘thin the blood’, such as warfarin, aspirin, rivaroxaban or clopidogrel. It is likely you will need to stop taking them before your operation as they increase the risk of bleeding. Taking medication like non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) could also increase your risk of bleeding and your surgeon will advise you if you need to stop taking these in advance of your operation. If your operation is scheduled with only a week’s notice, please check with you consultant or nurse what drugs need to be stopped to prevent your surgery being delayed.

- Difficulty with screw placement or screw breakage during surgery. Incorrect positioning of screws can occur in 2 out of 100 cases and could cause injury to the nerves. Breakages of the screw or rods can also happen, occasionally several months after surgery.

- Bone graft non-union or lack of solid fusion (pseudoarthrosis). This can occur in up to 5 out of 100 cases. See page 21 for factors which can affect fusion.

- Cage / Implant movement can occur in up to 2 out of 100 cases, with 1 out of 100 requiring re-operation. In extremely rare cases, cage movement can cause severe damage and cauda equina syndrome or spinal cord damage (paralysis, bladder or bowel incontinence).

- Although rare, the surgery may make your symptoms worse than before.

- Ongoing pain. Fusion surgery is a complex procedure and not all patients get pain relief.

There are also very rare but serious complications that in extreme circumstances might include:

- damage to the spinal cord or cauda equina resulting in paralysis (the loss of use of the legs, loss of sensation and loss of control of the bladder and bowel). This can occur through bleeding into the spinal canal after surgery (a haematoma). If an event of this nature were to occur, every effort would be made to reverse the situation by returning to theatre to wash out the haematoma. Sometimes, however, paralysis can occur as a result of damage or reduction of the blood supply to the nerves or spinal cord and this is, unfortunately, not reversible;

- a stroke, heart attack or other medical or anaesthetic problems;

- and extremely rarely, death; as a result of damage to major blood vessels or vital organs at the front of the spine, which is reported as happening in 1 out of 10,000 cases;

- general anaesthetic fatal complications which have been reported in 1 out of 250,000 cases.

ALIF specific risks and complications

- Damage to the large blood vessels which may result in excessive blood loss. This is reported as happening in up to 15 out of 100 cases, although it is less common in the hands of an experienced spinal or vascular surgeon. Usually small tears in the vessels can be controlled reasonably simply, though there remains the very small risk of catastrophic bleeding that could, in extremely rare circumstances, lead to death.

- Sympathetic nerve damage. There are small nerves directly over the disc space which can be damaged during surgery. These nerves are responsible for many involuntary organ functions, including the heart rate, peristalsis (gut movement), kidney function and, in men, the ability to ejaculate. If these nerves are damaged it can cause problems including:

- retrograde ejaculation (men only). This is a condition where the valve that causes the ejaculate to be expelled outward

during intercourse does not work and the ejaculate takes the path of least resistance, which is up into the bladder. The sensation remains largely the same and this condition does not cause impotence (the ability to have an erection) but it can unfortunately make conception very difficult. This is reported in fewer than 1 in 100 cases and can resolve over time (a few months to a year);

- warm leg. This sensation is felt in just one leg, the same side as the surgery has been performed. This can resolve over time but may be a permanent sensation;

- paralytic ileus. This is a condition where there is an interruption of the normal bowel contraction and the bowel temporarily ‘goes to sleep’. It can be a common side effect of abdominal surgery or nerve damage in this type of surgery. Symptoms include constipation and bloating and occasionally vomiting. Diagnosis can be confirmed by a doctor listening to the abdomen with a stethoscope and hearing no bowel sounds. Food should be avoided until sounds are heard and flatus (gas) passed again. This condition can occur in 11 out of 100 cases.

- Abdominal muscle weakness/hernia/bowel perforation/intra-abdominal organ injury/ bowel perforation/.

LLIF / XLIF specific risks and complications

- Damage to nerves which could result in thigh pain and / or numbness and weakness of the muscles involved with hip flexion, which may be temporary or permanent.

Abdominal muscle weakness/hernia/bowel perforation/intra-abdominal organ injury/ bowel perforation/.

OLIF specific risks and complications

- Damage to the large blood vessels which may result in excessive blood loss. This is reported as happening in up to 15 out of 100 cases, although it is less common in the hands of an experienced spinal or vascular surgeon. Usually small tears in the vessels can be controlled reasonably simply, though there remains the very small risk of catastrophic bleeding that could, in extremely rare circumstances, lead to death.

- Sympathetic nerve damage. There are small nerves directly over the disc space which can be damaged during surgery. These nerves are responsible for many involuntary organ functions, including the heart rate, peristalsis (gut movement), kidney function and, in men, the ability to ejaculate. If these nerves are damaged it can cause problems including:

- retrograde ejaculation (men only). This is a condition where the valve that causes the ejaculate to be expelled outward during intercourse does not work and the ejaculate takes the path of least resistance, which is up into the bladder. The sensation remains largely the same and this condition does not cause impotence (the ability to have an erection) but it can unfortunately make conception very difficult. This is reported in fewer than 1 in 100 cases and can resolve over time (a few months to a year);

- warm leg. This sensation is felt in just one leg, the same side as the surgery has been performed. This can resolve over time but may be a permanent sensation;

paralytic ileus. This is a condition where there is an interruption of the normal bowel contraction and the bowel temporarily ‘goes to sleep’. It can be a common side effect of abdominal surgery or nerve damage in this type of surgery. Symptoms include constipation and bloating and occasionally vomiting. Diagnosis can be confirmed by a doctor listening to the abdomen with a stethoscope and hearing no bowel sounds. Food should be avoided until sounds are heard and flatus (gas) passed again. This condition can occur in 11 out of 100 cases.

Factors which may affect spinal fusion and your recovery

There are several factors that can negatively impact on a solid fusion following surgery, including:

- smoking

- diabetes or chronic illness

- obesity

- malnutrition

- osteoporosis

- post-surgery activities (see note on recreational activities)

- long-term (chronic) steroid use.

Of all these factors, the one that can compromise fusion rate the most is smoking. Nicotine has been shown to be a bone toxin which inhibits the ability of the bone-growing cells in the body (osteoblasts) to grow bone. Patients should make a concerted effort to allow their body the best chance for their bone to heal by not smoking, ideally 2 – 3 months before the operation. Your surgery may be delayed if you have not stopped smoking (or taking nicotine in another form) beforehand.

What to expect after surgery and going home

Immediately after the operation you will be taken on your bed to the recovery ward where nurses will regularly monitor your blood pressure and pulse. Oxygen will be given to you through a facemask for a short period to help you recover from the anaesthetic. You will have an intravenous drip until you can drink adequately.

A drain (tube) may be placed near the surgical incision if there has been significant bleeding during the operation. This removes any excess blood or fluid collecting under the wound. The drain will be removed when the drainage has stopped, usually the next day after surgery.

It is very normal to experience some level of discomfort or back and leg pain after the surgery. The nursing and medical staff will help you to control this with appropriate medication. The symptoms in your legs may fluctuate due to increased swelling around the nerves. As the nerves become less irritated and swollen, your leg pain should settle. This can take eight weeks, or longer. Normal feeling and strength in your legs is likely to take a lot longer and is likely to improve slowly over the next year or so. It is important not to suddenly stop taking certain pain relief medication such as morphine, or neuropathic medication (gabapentin, pregabalin or amitriptyline). It will be necessary to gradually ‘wean’ yourself off these medications – your GP can advise you if necessary.

The ward physiotherapist will visit you after the operation to teach you exercises and help you out of bed. They will show you the correct way to move safely. Once you are confident and independently mobile, you will be encouraged to practise climbing stairs with the physiotherapist. Once stable, you will be allowed home, usually 1 – 2 days after surgery.

Please arrange for a friend or relative to collect you, as driving yourself or taking public transport is not advised in the initial stages of recovery. If you qualify for patient transport and are likely to require this service, please let one of the nurses know as soon as you can as this may need to be pre-arranged. Your discharge home could be delayed if not.

Wound care

Skin wound closure depends on your surgeon’s preference, and include absorbable sutures (stitches), removable sutures or clips (surgical staples).

If you have removable sutures or clips, you will be seen by a nurse to remove them usually 10–14 days after the operation in the outpatient department. If you have absorbable sutures, these still may need to be trimmed and you will still require a wound check to be taken out.

The ward staff or consultant secretary will inform you of the date for your appointment or if you prefer to make an appointment with your GP practice nurse.

You may shower 48 hours after surgery if you are careful, but you must avoid getting the wound wet. Most dressings used are ‘splash-proof’, but if water gets underneath, it will need to be changed, a simple, dry dressing from a pharmacy is sufficient to use if a new dressing wasn’t provided on discharge, please make an appointment in this instance for a wound check and re-dressing with outpatients’/specialist nurse. Bathing should be avoided for a minimum of two weeks.

Please contact your hospital if you think your wound might be infected. Symptoms could include:

- redness around the wound;

- wound leakage;

- a high temperature or

- Increased pain at wound site

At a later stage once the wound has healed and been checked, if the scar is sensitive to touch, you can start to massage around the scar using an unperfumed cream or oil to encourage normal sensation and healing.

Driving

Normally you will be advised to avoid driving for four weeks (or when you no longer require the brace, if you have been provided with one), depending on your recovery.

If you have no altered sensation or weakness in your legs at that point, then you may resume driving if you feel safe to do so, but you must be confident to do an emergency stop.

It is advisable not to travel for long distances initially (no longer than 20 minutes), without taking a break to ‘stretch your legs’. Gradually increase your sitting tolerance over 4 – 8 weeks.

Recreational activities

It is important to keep mobile after surgery. You will find you get stiff if sitting for longer than about 20 minutes, so get up and walk about regularly. Walking outside is fine but again, increase your walking distances gradually.

You will be advised to avoid lifting anything heavy, certainly for the first few weeks but maybe for as long as three months after your operation.

Please check with your consultant when you are able to resume specific activities, such as swimming or running, as the advice could range from between two weeks to three months. A gradual return to sport is then advisable. You should avoid flying for six weeks (and long-haul flights for up to three months). If you are provided with a LSO lumbar brace wear this for the length of time your consultant has advised (usually 6 weeks) when mobilising.

Work

Returning to work is dependent on both your recovery and your job. Most people are off work for an initial four weeks but if you are in a strenuous job you may need up to eight weeks. It is always sensible to discuss with your employer if you can return on ‘light duties’ or reduced hours at first. There is usually nothing to stop you doing computer / office work at an earlier date provided you can keep moving about. The hospital will issue you with a fitness to work (off work) certificate or you may ask your GP.

Follow-up

Your surgeon will advise you when you should attend clinic after your operation. If you have any queries before your follow-up date do, please contact the nurse specialist or other member of your consultant’s team. If you have any questions about the information in this booklet, please discuss them with the ward nurses or a member of your consultant’s team.

Information in this leaflet is based on research and revised by spinal nurse specialist Helen Vernau on behalf of the BASS Consent and Patient Information Committee. Illustration by Design Services at The Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust. Edited by Consultant Neurosurgeon Mr Rafid Al-Mahfoudh and Spinal Clinical Nurse Specialist Sara Crook with permission from BASS to be used at the Nuffield Brighton Hospital.

What is the British Spine Registry (BSR)?

The British Spine Registry aims to collect information about spinal surgery across the UK. This will help us to find out which spinal operations are the most effective and in which patients they work best. This should improve patient care in the future.

The Registry will enable patient outcomes to be assessed using questionnaires. These will allow surgeons to see how much improvement there has been from treatment.

This has worked for hip and knee joint replacements through the National Joint Registry. We need your help to improve spinal surgery in the UK.

What data is collected?

Your personal details allow the BSR to link you to the surgery you have had. They also allow us to link together all the questionnaires you complete. If you need any further spinal surgery in the future, details of previous operations will be available to your surgeon.

Personal details needed by the BSR are your name, gender, date of birth, address, email address and NHS number.

Your personal details are treated as confidential at all times and will be kept secure. This data is controlled by the British Association of Spine Surgeons (BASS) and held outside the NHS. Personal details will be removed before any data analysis is performed, retaining only age and gender. Your personal data and email address will not be available to anyone outside BASS and its secure IT provider. Anonymised data may be released to approved organisations for approved purposes, but a signed agreement will restrict what they can do with the data so patient confidentiality is protected.

Your personal data is very important, as this will allow us to link details of your diagnosis and surgery with any problems or complications after surgery. You may also be asked to complete questionnaires before and after surgery to work out how successful the surgery has been. This will only be possible if we can connect you to the questionnaires through your personal details.

I have to give consent?

No, your participation in the BSR is voluntary and whether you consent or not, your medical care will be the same. Your personal details cannot be kept without your consent. This will be obtained either by asking you to physically sign a consent form or electronically sign one through an email link to a questionnaire or at a questionnaire kiosk in the outpatient clinic.

You can withdraw your consent at any time or request access to your data by:

- going to the patient section of the BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com; or

- writing to us at the BSR centre (see address on next page). Please state if you are happy for us to keep existing data but do not want to be contacted, or whether you want your data to be anonymised (so it cannot be identified).

Research

Your consent will allow the BSR to examine details of your diagnosis, surgical procedure, any complications, your outcome after surgery and your questionnaires. These are known as ‘service evaluations’ or ‘audits’.

Operation and patient information, including questionnaires in the

BSR, may be used for medical research. The purpose of this research is to improve our understanding and treatment of spinal problems. The majority of our research uses only anonymised information which means it is impossible to identify individuals. From time to time, researchers may wish to gather additional information. In these cases we would seek your approval before disclosing your contact details. You do not have to take part in any research study you are invited to take part in and saying no does not affect the care you receive.

All studies using data from the Registry will be recorded on the BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com

Further information

The BSR website at www.britishspineregistry.com contains more information, including details of any studies and any information obtained through the Registry data.

To contact the BSR, write to:

The British Spine Registry

Amplitude Clinical Services

2nd Floor

Orchard House

Victoria Square

Droitwich

Worcestershire WR9 8QT